BORA BASKAN

BORA BASKAN

[Chapter 6]

Welcome back to the Creative Minds Project with a very special guest, the one and only Bora Baskan.

Bora Baskan is an Istanbul-based multidisciplinary artist whose work has been exhibited in Istanbul, Paris, Berlin, Barcelona, and Los Angeles. Bora and I first met in Berlin when he had just moved there, and at the time, we both related deeply to the experience of being outsiders in a new city. Over the years, our paths almost crossed in tangential ways, which is perhaps surprising given that we were born and bred on the same streets, shaped by similar neighbourhoods, rhythms and histories of Istanbul.

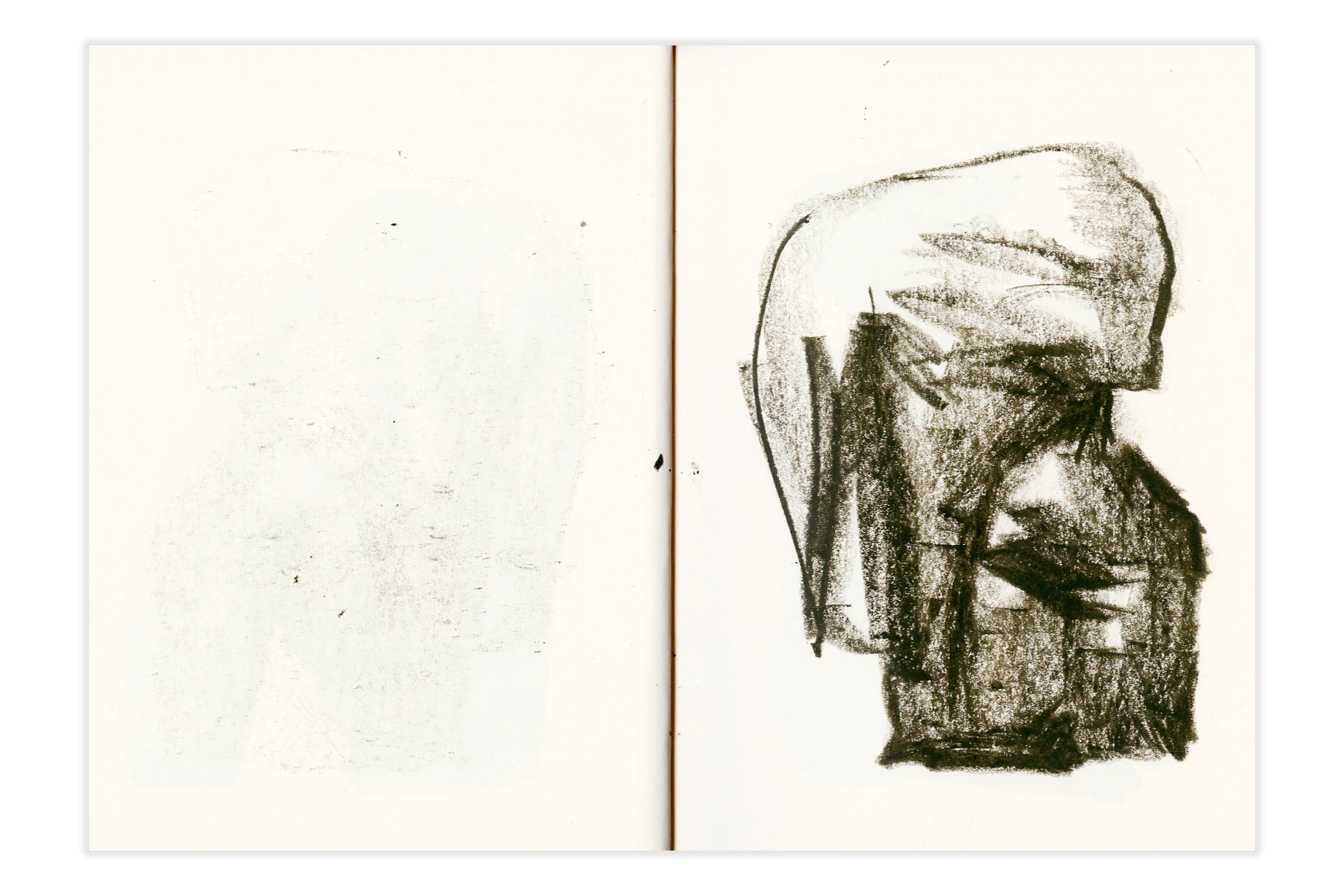

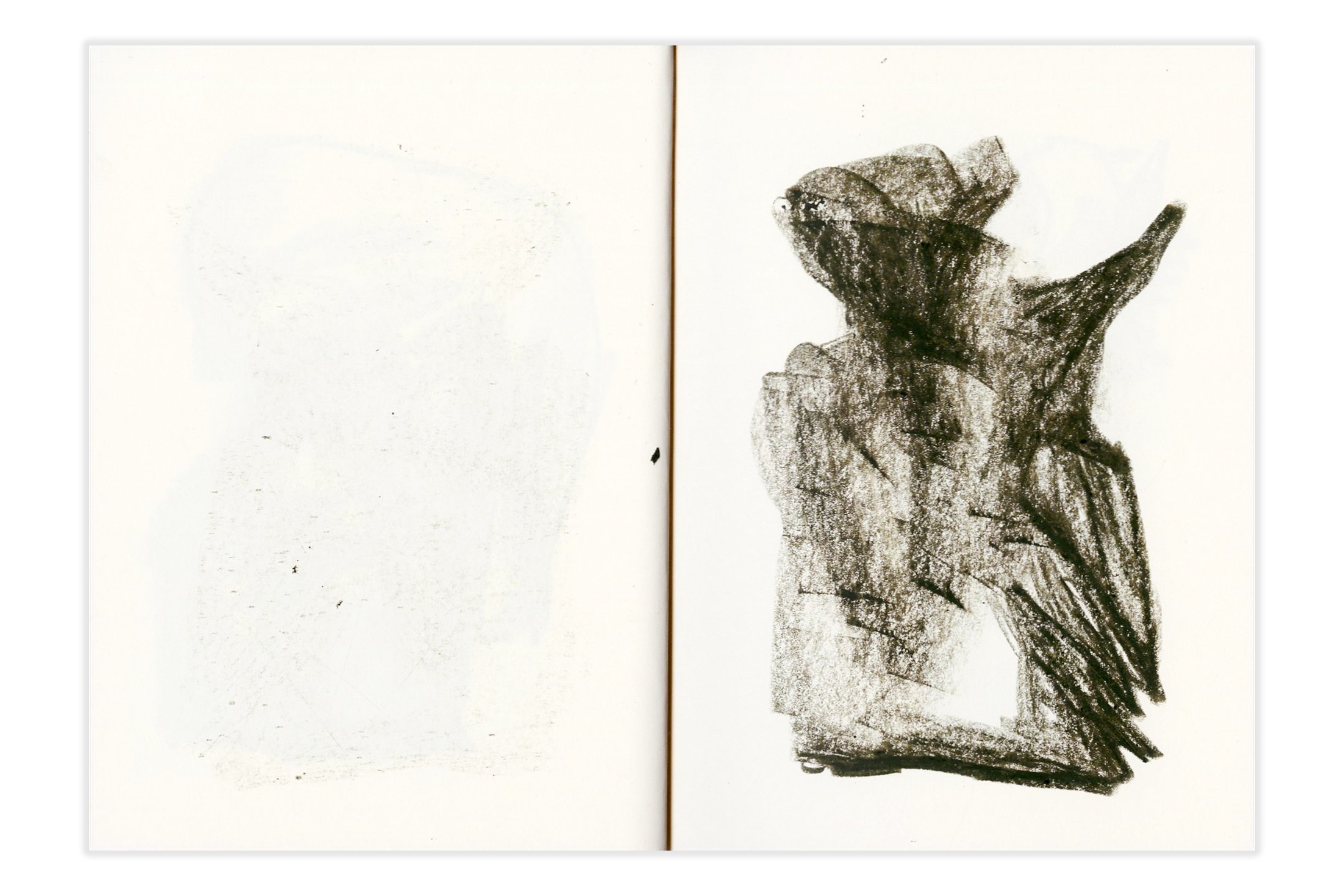

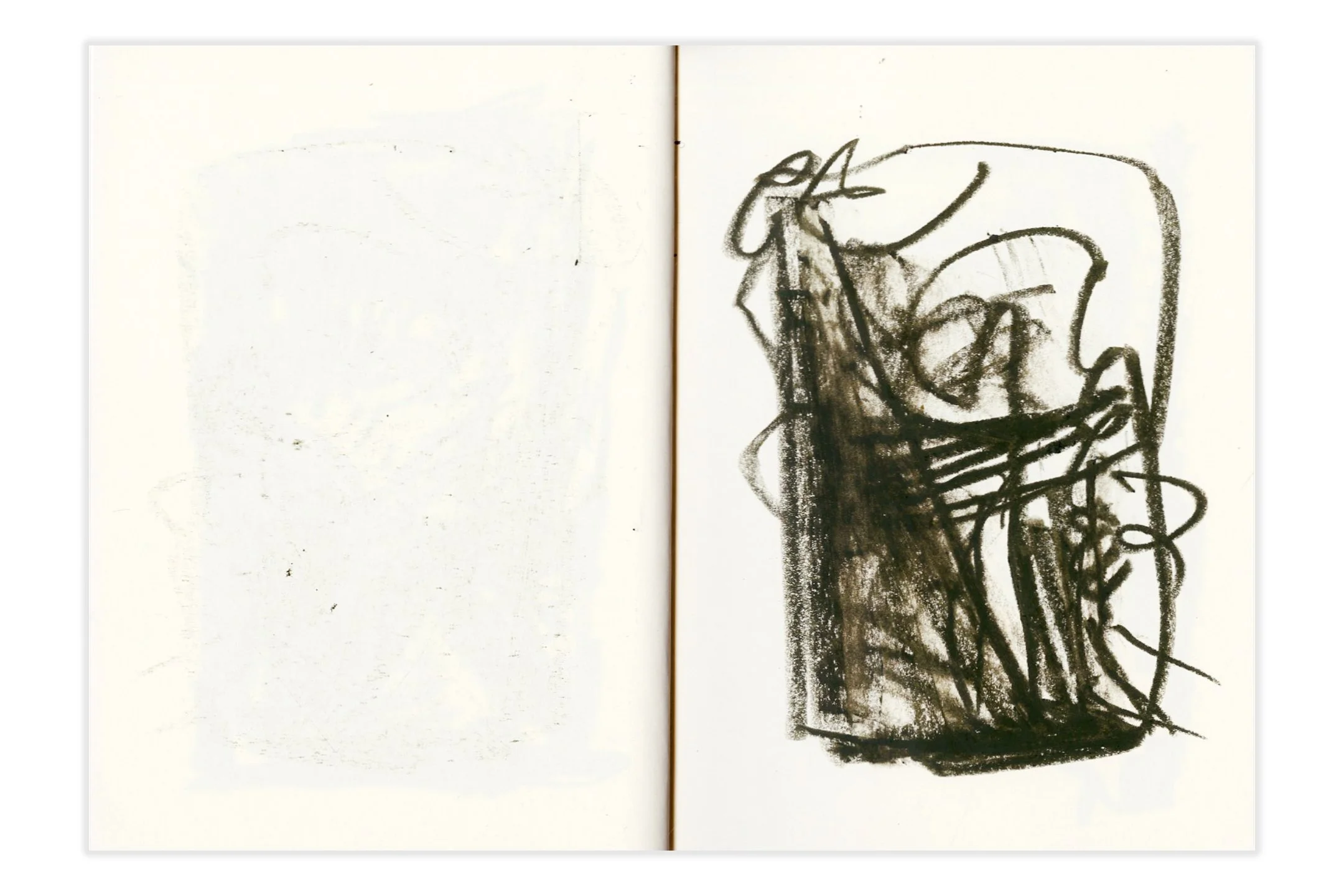

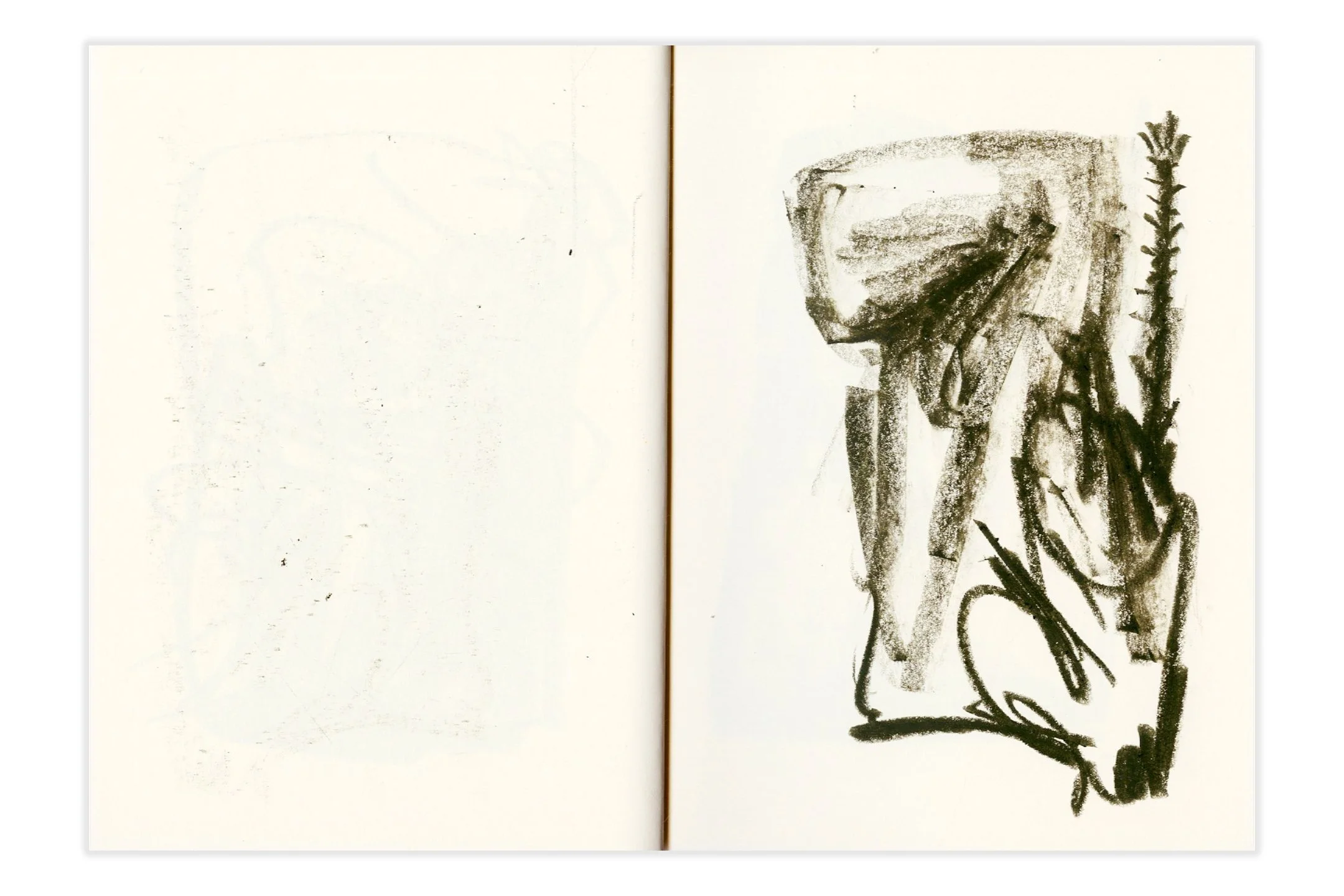

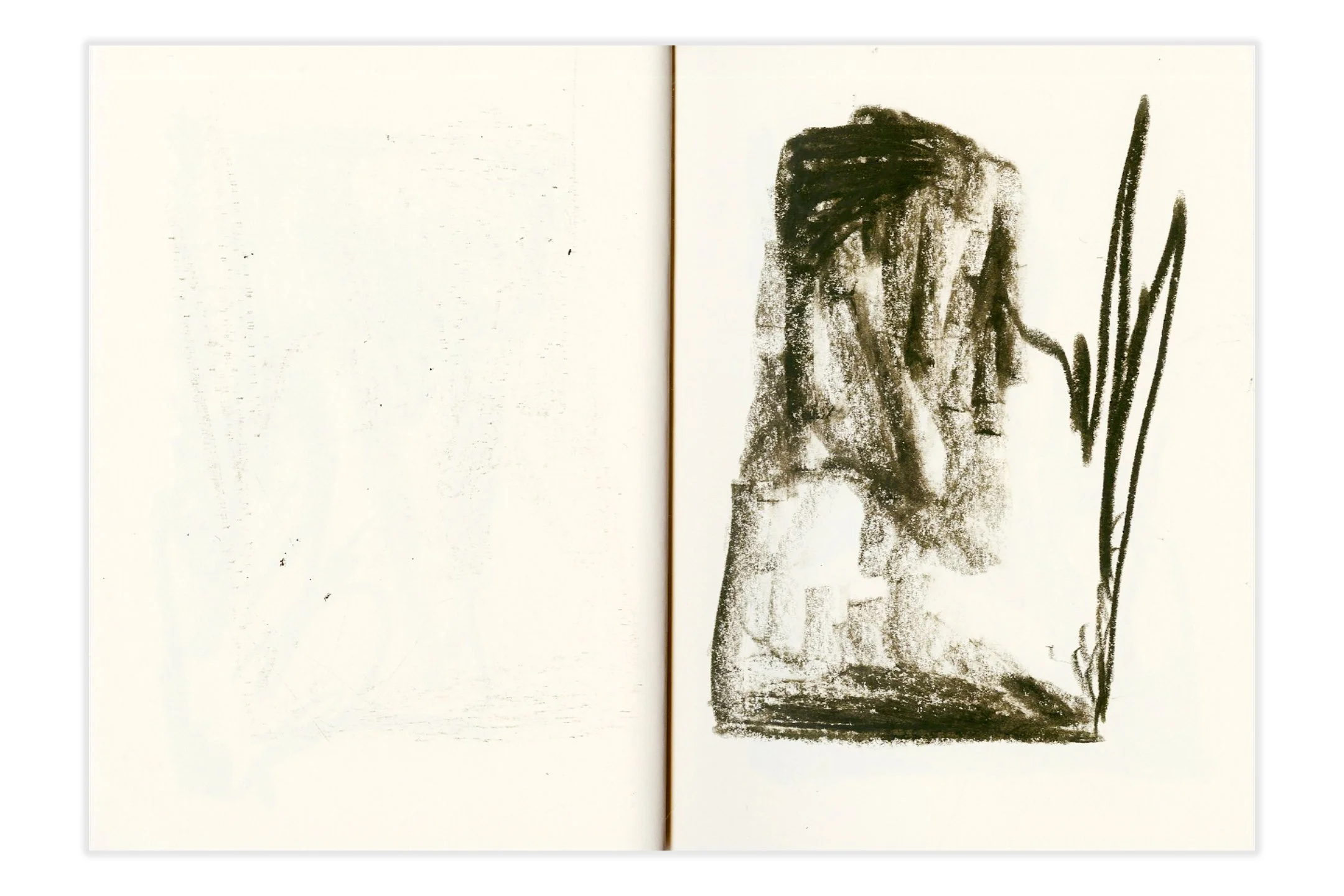

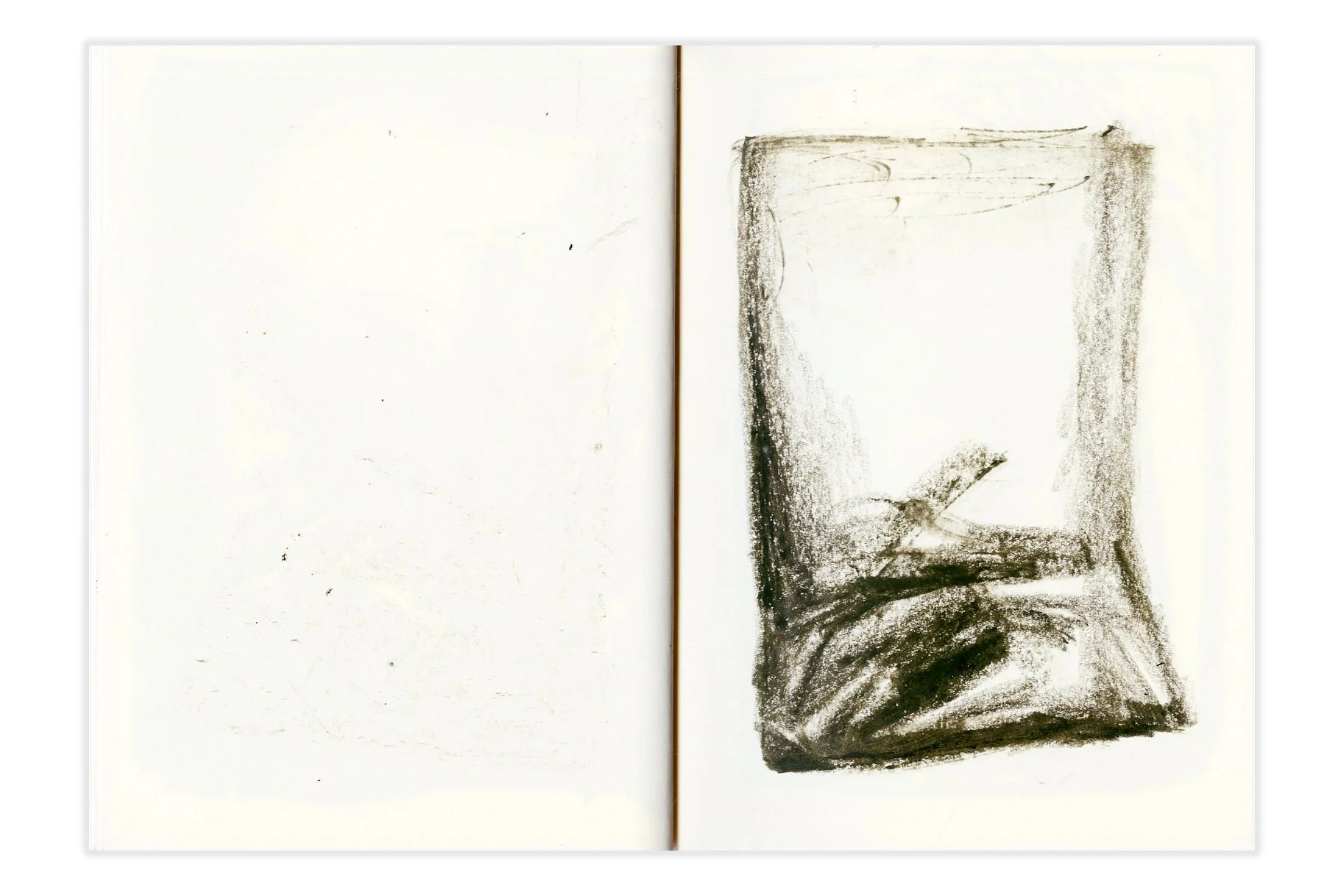

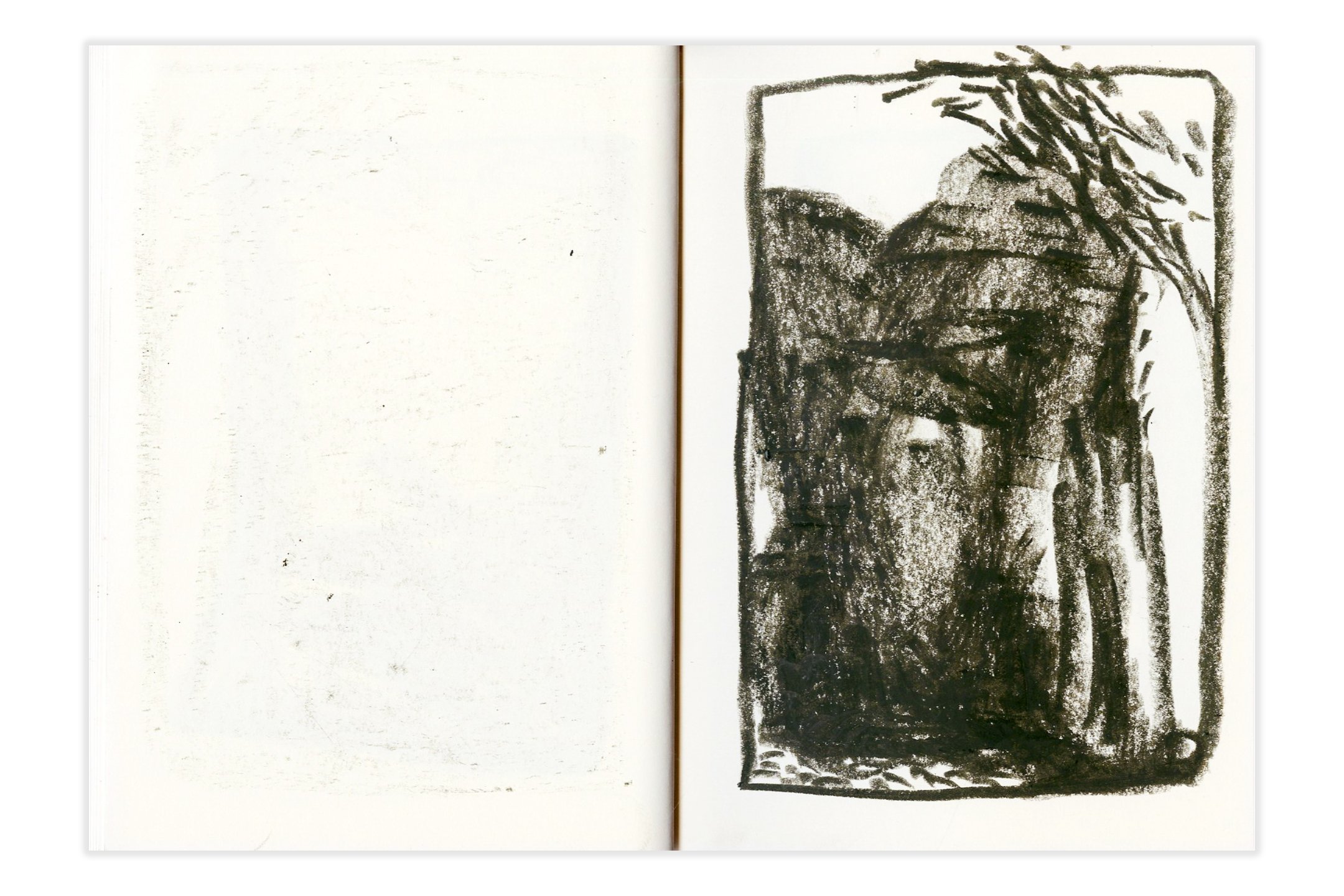

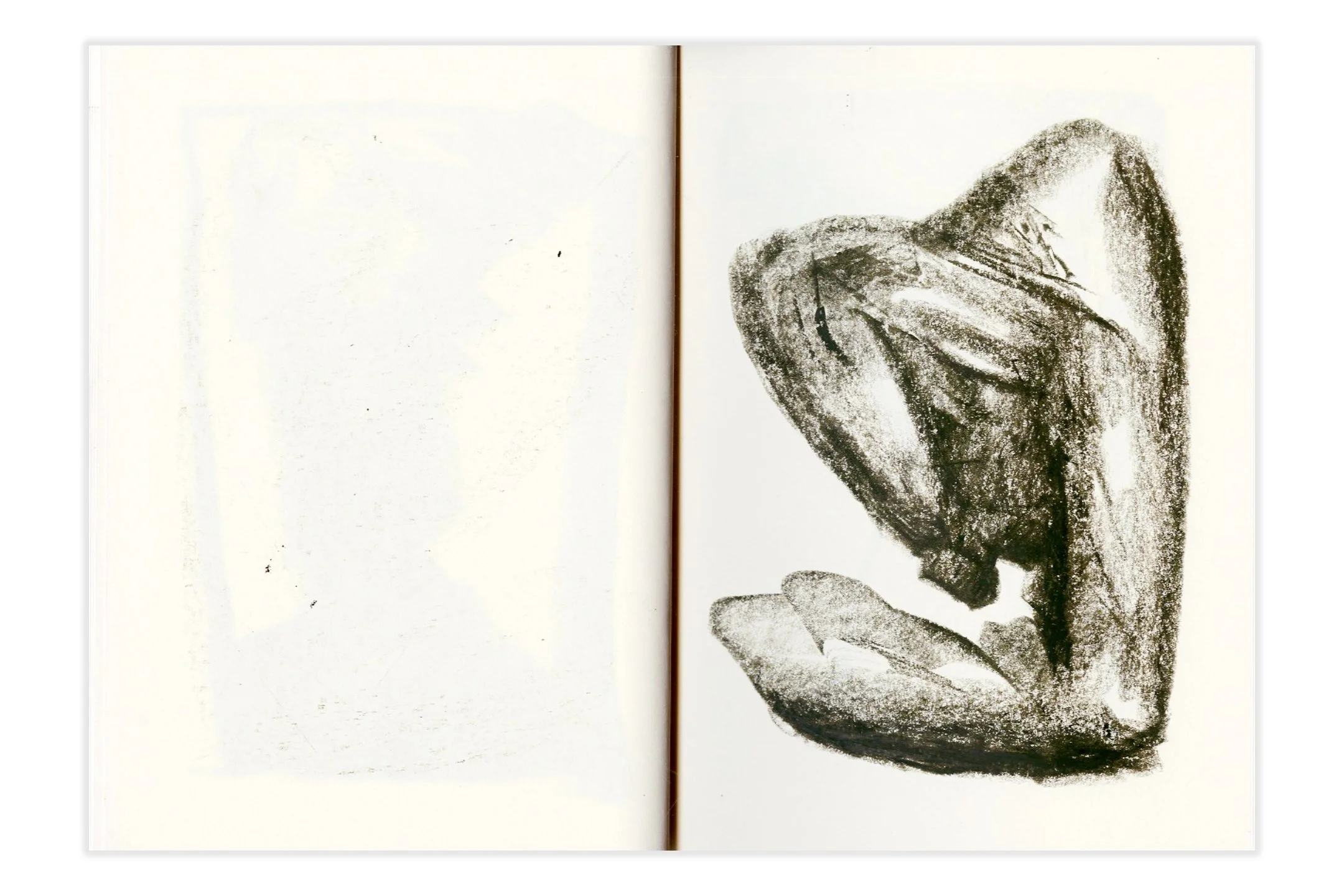

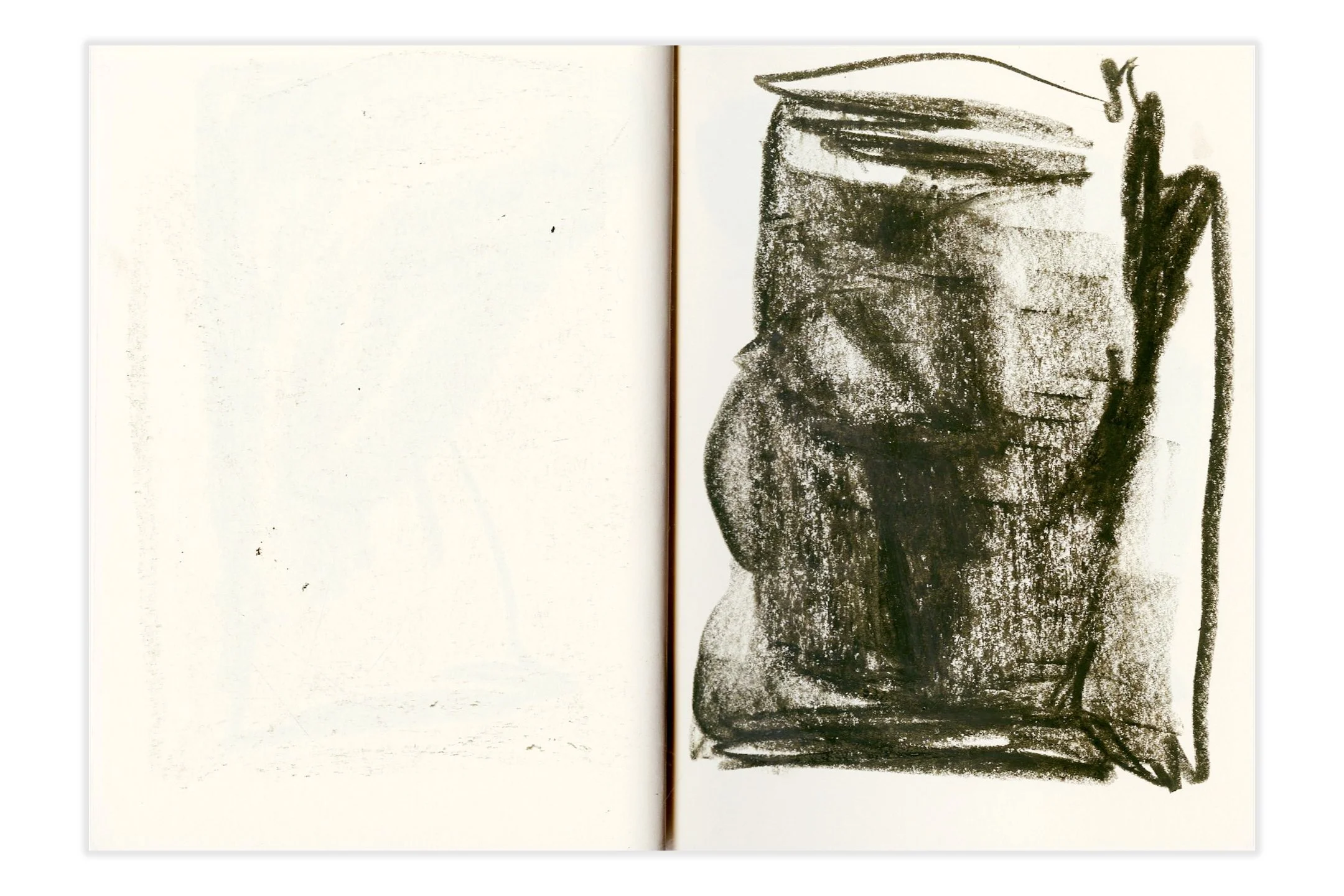

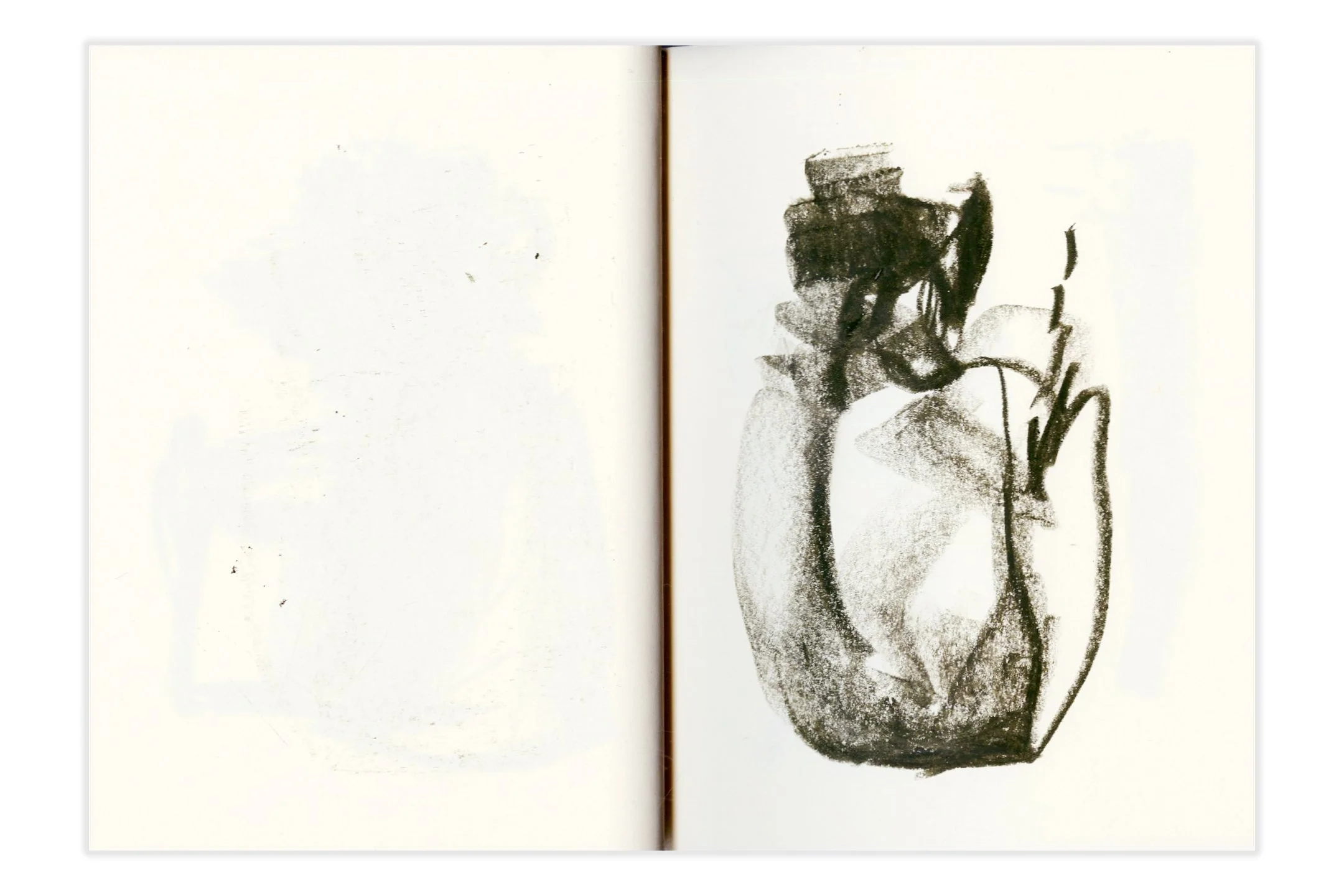

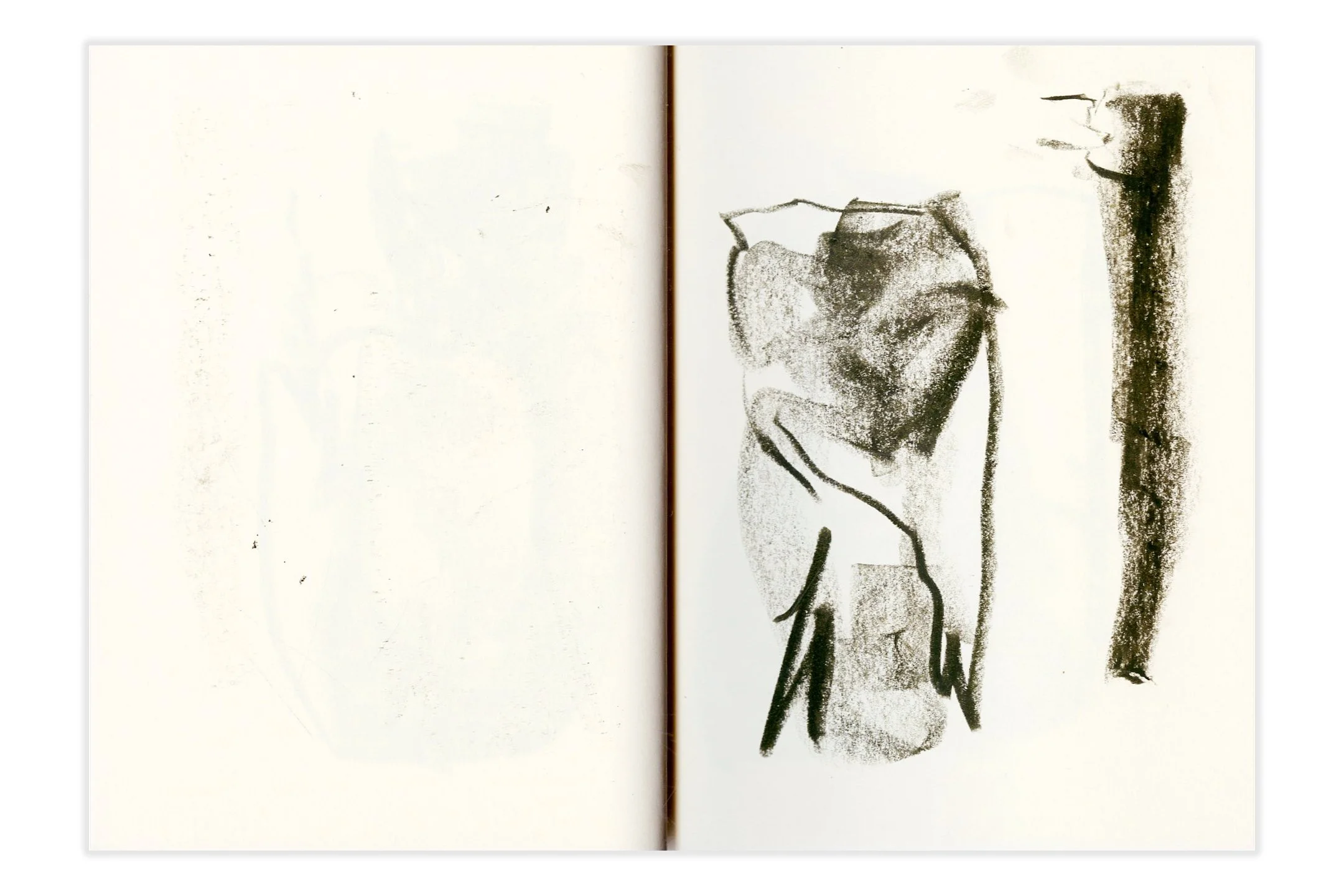

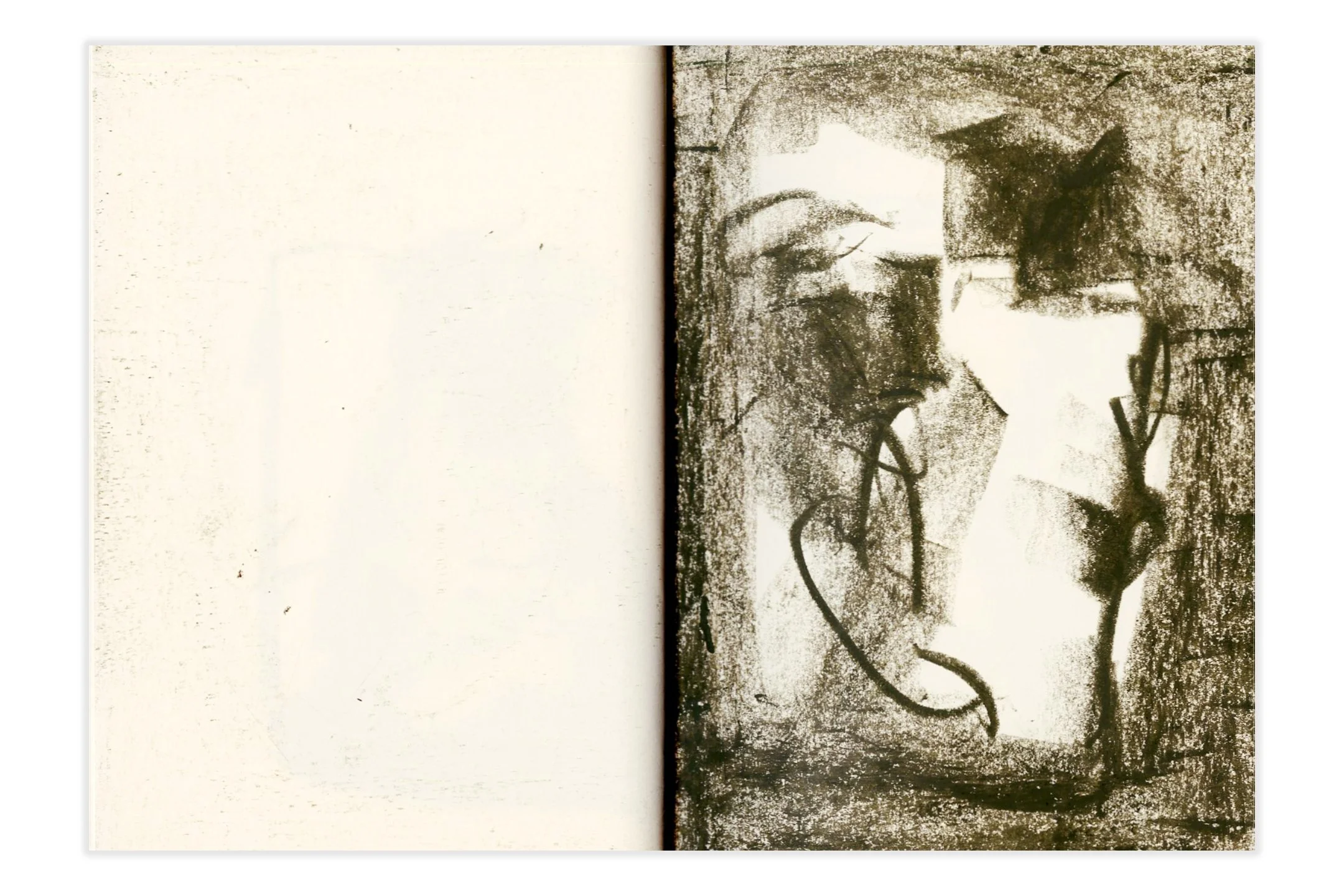

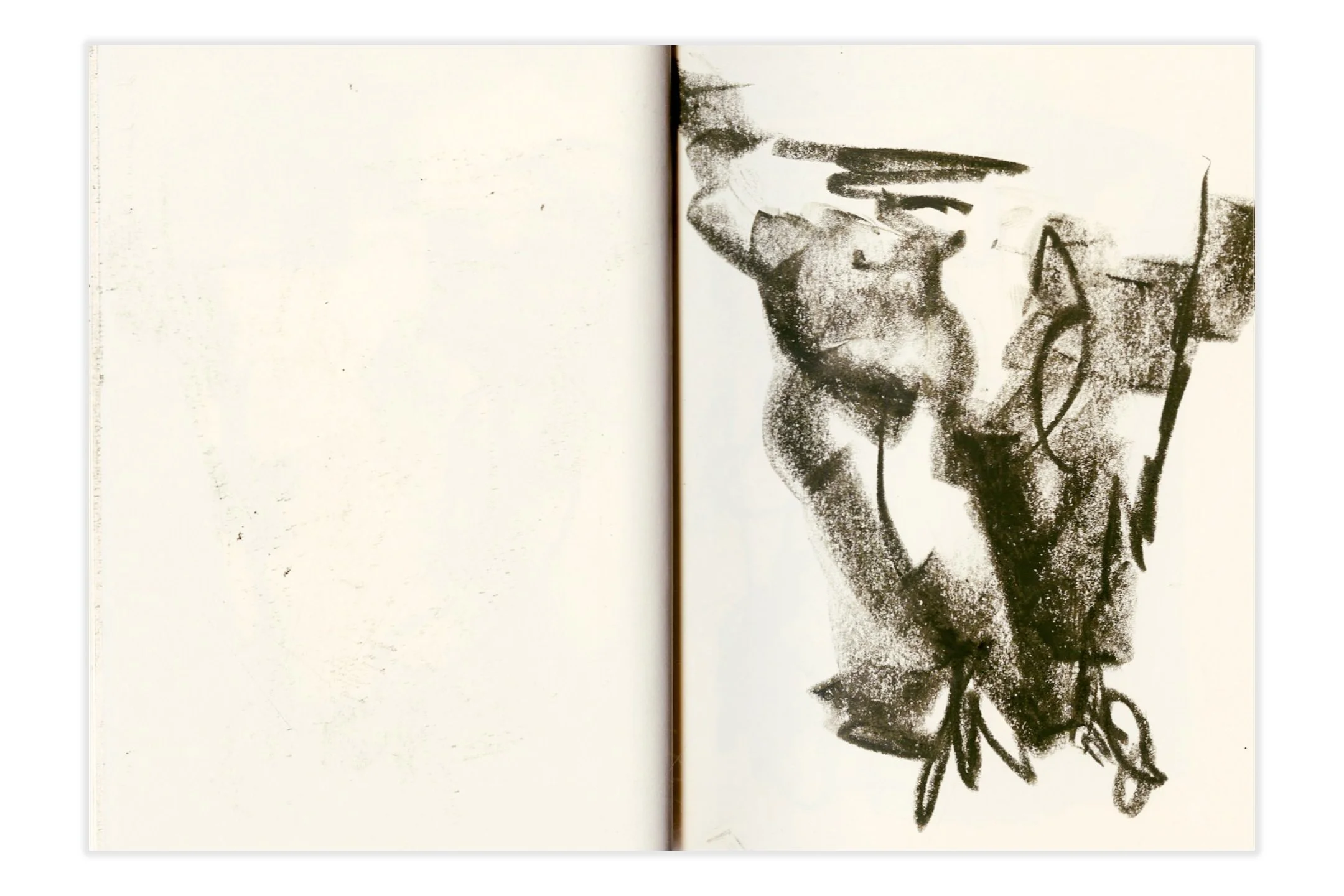

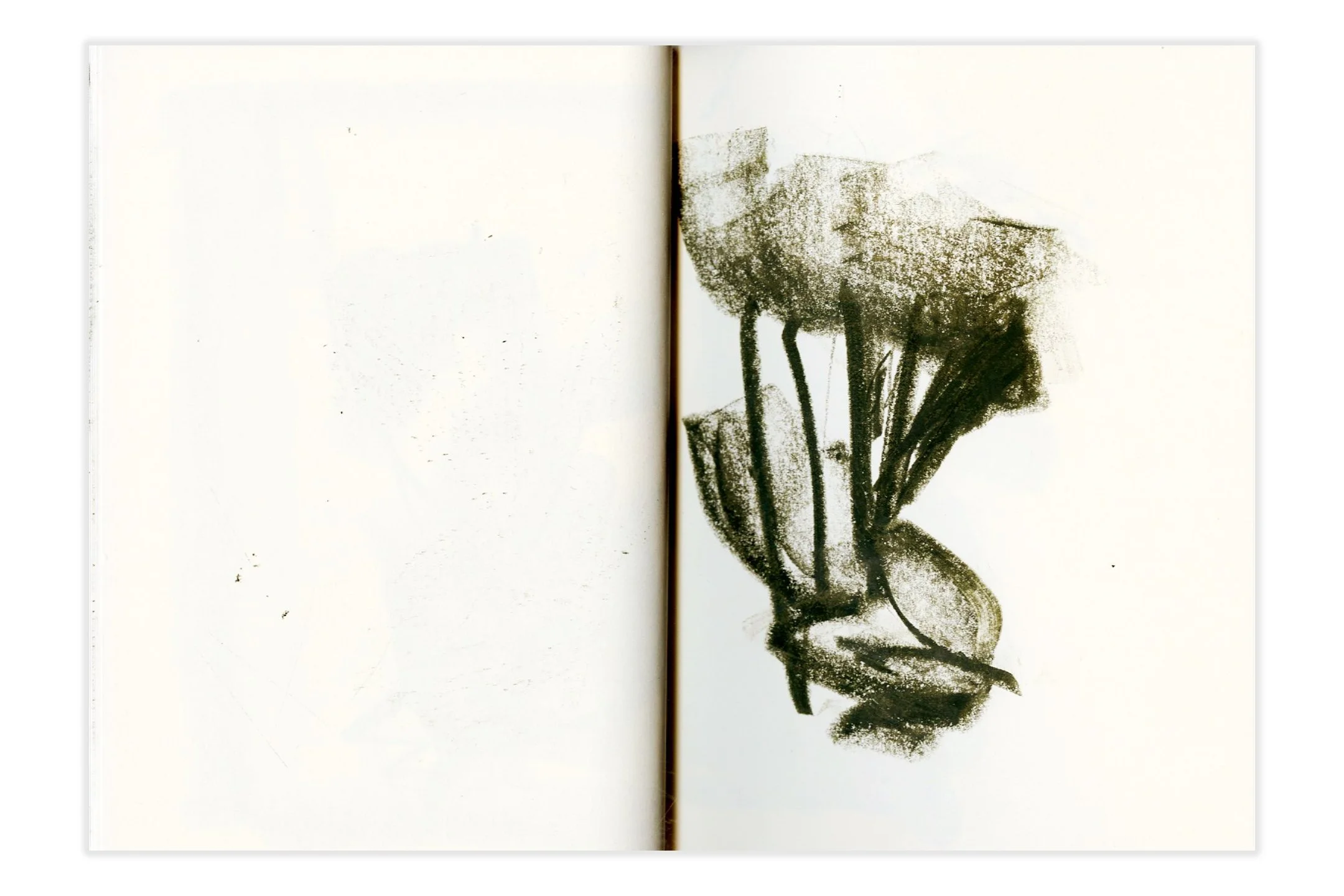

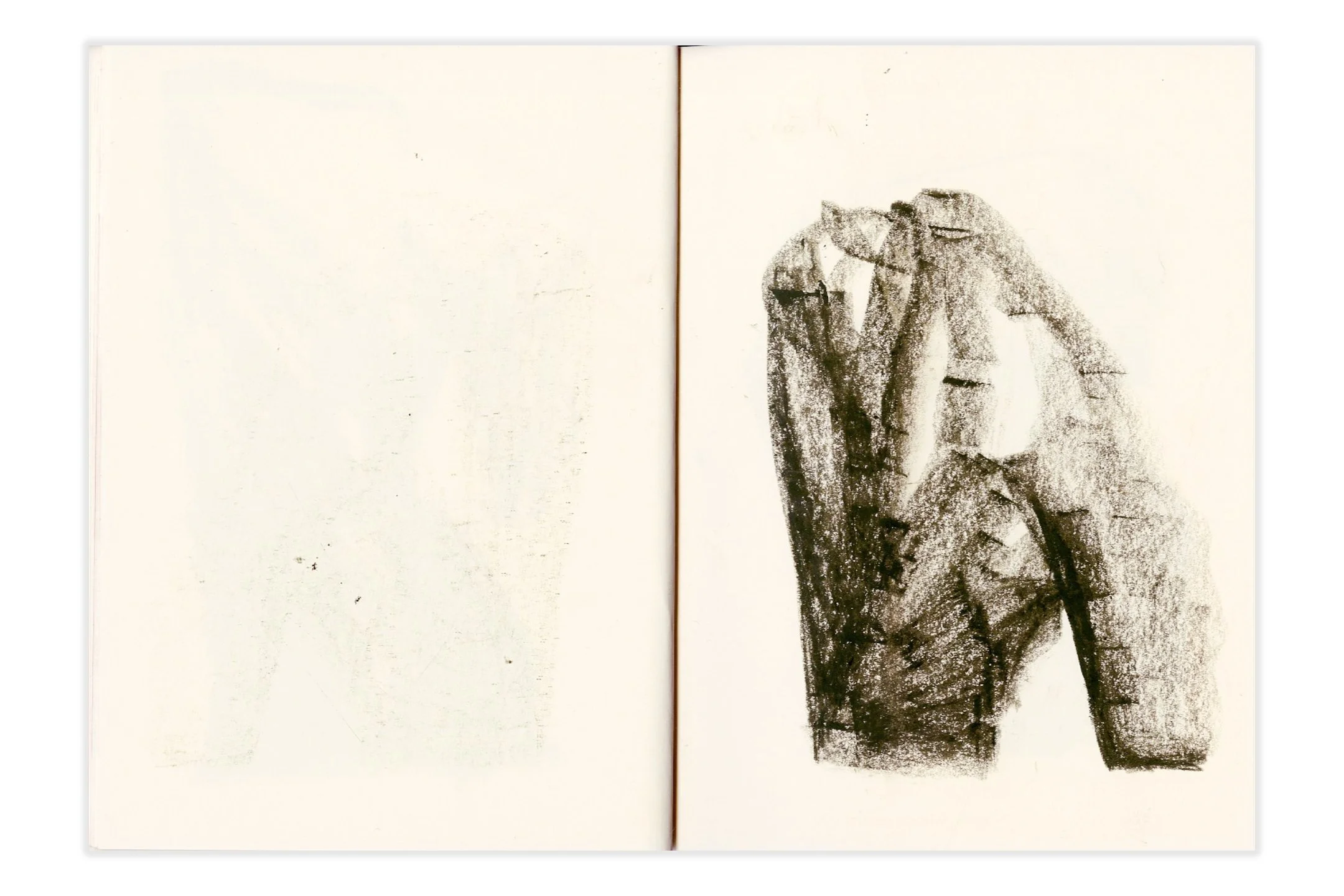

Bora is one of the most promising contemporary Turkish artists whose intellectual depth is matched by an understated generosity for his craft. Trained as a graphic designer and now working primarily in drawing and painting, he explores the fluid boundaries between the organic and the mechanical, the political and the phenomenological, and the formation and dissolution of form. His practice is thoughtful, uncompromising and philosophically grounded, and it is truly an honour to have this rare sketchbook in our archive.

For the Creative Minds Project, Bora created a notebook that is as raw and instinctual as it is reflective. I am excited to share the pages he contributed, along with our conversation about art, migration, abstraction, and the visible and invisible systems that shape us. I hope you enjoy this glimpse into Bora’s reflective inner world and his careful, iterative process as much as I did.

Q: We met when you first moved to Berlin. I’d love to begin by checking in on your experience, a few years in. How has Berlin shaped your life and your art so far?

Q: Looking back at your university years, can you share a bit about your journey from studying graphic design to becoming a visual artist?

Q: How did the design education help you find your artistic voice? And are there pieces of wisdom from your formal training that you still carry into your practice today?

A: As you said, when we first met, I was still fairly new to Berlin and had rather naïve expectations. As an immigrant, attaching hopes to a new city is one of the more difficult things. At the same time, the process of becoming an immigrant is where the biggest learnings happen. I didn’t stay there long enough to experience the kind of transformation it demanded; I didn’t fully adopt it, nor did I want it to permeate my life further. It’s an environment and a culture quite distant from the things I seek and value. I don’t think it has influenced my work. It has influenced me, though. There’s the long-standing dilemma of the Turkish expat who has spent over a century searching for enlightenment in the “West.” Realising this has been the greatest lesson for me. I no longer seek anything in the West, as it comes from this delusional thinking, “If only they knew us, they would like us.”

A: My interest in the visual arts began long before university. Actually, “began” isn’t even the right word, I was simply born into a world saturated with visual culture. Because of my father’s profession (he taught at the Academy of Fine Arts), our home was filled with books, magazines, and objects related to art: art history books on European movements, Anatolian civilizations, carpet motifs, Islamic calligraphy; drawings and engravings gifted by his colleagues; his own works; calligraphic abstractions; semi-reliefs; post-apocalyptic textile pieces; a bust of Alexander; a miniature tree made from dried olive branches; African masks my uncle brought from Paris. All of these objects formed a rich visual world around me when I was far too young to understand what any of them actually were.

The relationship between graphic design and music was especially critical during my university years. The early 2000s were a time when music videos and album covers were prominent, especially with the rise of electronic music. Within my school’s more classical approach to the arts, it was frustrating not to find much that reflected the audiovisual graphic world that inspired me. Still, it was a valuable period for learning basic design principles, questioning why I made what I made, and building a foundation in art and design history. I spent those years oscillating between traditional education and the freedom encouraged by some more open-minded professors. Music played a central role in that period and still does, though not as intensely.

A: Even while studying graphic design, my relationship with drawing and painting was stronger than my relationship with design itself. I wanted to position myself somewhere between the two disciplines. Looking back now, the illustration and design influences in my paintings gradually diminished, while painterly qualities increased in my design work. The two fields nourished one another and blurred each other’s boundaries. I’ve never believed that the line between commercial graphic design and art should be as clearly drawn as it often is. Historically, it may have been necessary, but today I think it should be redefined. In my painting practice, I behave more like a designer, and in my design practice, more like a painter.

Q: Your work often merges surreal forms and abstraction, blurring organic into mechanical. What draws you to these themes, and how has your point of view evolved over time?

A: I remember being deeply influenced by the Surrealists and Dadaists as a child. I still reflect on that early influence, trying to understand how it shaped me then, and how it continues to surface subconsciously in the forms I create. Over time, I think I’ve moved away from the organic/mechanical polarity that was especially prominent in Dada and Surrealism (and understandably so given the time period). In recent years, I’ve been more interested in the transience of imagery, the fluidity of objects, and the impossibility of producing an image with clearly defined, graspable boundaries. The organic/mechanical duality is a formal and structural concern; the formation and dissolution of the image is more phenomenological. Naturally, my work has evolved in that direction as well. And part of this came from trying to avoid a self-centred formal perspective. My life has also shifted this way, though that part is harder to articulate.

Q: Your 2015 solo exhibition, Savage Humanchine, followed a male robot bound to the rules of an oppressive system. Yet you seemed to reclaim a sense of optimism in your vision of the future then. Where do you stand today, a decade later, in the midst of the current technological revolution?

A: I’ve never been interested in the world we see on social media. Our presence on this platform is far too brief to make broad observations about the world, especially the version we encounter through images, videos, and likes. I don’t even think a direct relationship with life is possible anymore. That’s why I increasingly look back at how people once engaged with the world.

Throughout human history, we’ve always experienced a form of technological conflict. Believing that the era we live in is uniquely special is narrow-minded; a time-based illusion. I find the glorification of our current moment exaggerated. AI, wars, and the desire to cross new thresholds or rewrite history have reached a tragic point, when in fact history repeats itself constantly. It’s also true, of course, that progressive cultures tend to survive longer. But this idea of “learning from history” may not hold much significance at the larger scale when we consider cultures and civilizations. Those that stumble, even briefly, are erased quickly.

When I spoke of a “robot,” I was referring to a Spinozist concept of the human—a spiritual automaton—rather than a factory machine. It was a reference to the automation within our perception of life and many of our actions. Historically, masculinity has always been central to this automaton. Because of its biological predisposition to that role, it was rewarded within the system and wrote history through war. I’m speaking of a technological war as much as a mythological one. Art has long been a mythic arena where techno-fetishism is sanctified. These seductive spaces prepare society for more progressive post-control practices, presenting wild ideas in their most alluring forms. Still, I’m neither pessimistic nor optimistic.

The anxiety around new technologies is an economic one, and therefore existential. Outside of commercial work, I don’t feel compelled to use these tools in my artistic practice. Eventually these tools, and their accelerating updates, begin to shape the practice itself. One ends up accepting the aesthetics they impose, even unconsciously. In my graphic design work, I explore the notion of “obsolescence.” I try to turn technology into a tool by making its limitations the subject. Becoming obsolete, falling behind, these already imply a kind of surrender. Once you accept that, the pressure of time is lifted off your shoulders. Producing the most progressive work, using the latest version, this speed is created by the market. How necessary is it for what I do? Especially when I’m already questioning that very speed.

Q: When you begin a new project, what does your process look like? Do you still avoid central narratives and work instead within multiplicities?

A: I’ve always had the instinct to avoid the centre. I increasingly believe that some tendencies arise not from learning but from nature, even genetics. We should ask ourselves: Who needs the centre? What is it for? As ordinary people, how much do we truly need it? Capital, politics, and military structures serve the same purpose, hence the tension between the centralised and the decentralised systems.

A: I don’t begin a project with the intention of visualising or translating concepts. But because I work in a semi-abstract space, ideas that linger and affect me inevitably reveal themselves in the underlying layers of what I make. I increasingly avoid explicit philosophical references. From the beginning, I’ve tried to capture a micro-phenomenological cross-section of things.

When you pose a formal question, there are many lenses through which to answer it, and politics is only one of them. How does political power manipulate form? What value does it assign to form? Which forms does it prefer? The phenomenology of form inherently contains political undercurrents. But if we claim that form exists only in the realm of politics, we wrongly exclude a vast section of visual culture.

In short, I’ve been trying to understand form, light, composition, and shadow. Politics and other intellectual fields are simply subcategories under the broader field of aesthetics. I don’t think anything can be more aesthetic than politics.

In the Tower of Babel story in the Torah, God descends to scatter human language so they cannot complete the tower that would reach the heavens. Language, in that narrative, is the fundamental requirement for organisation, and for reaching the divine. Although I don’t reference language directly in my work, when depicting a more fluid, transitional world, language plays an essential role. I try to depict a whole that is scattered not only visually but culturally. That’s why I mentioned the Torah story. How can such a whole be formed without language? This is where multiplicity comes in.

Q: What are you most excited about at the moment? Are there any projects you’re currently developing?

A: Thanks to my partner, our trips to East Asia have opened up new horizons. Social patterns, eating and drinking rituals, language, phonetics, etymology, even something as simple as how pavement stones are arranged, spark new questions in my mind.

At the same time, I’ve been reading about Thessaloniki and Istanbul from the perspective of a migrant. I’m looking into Middle Eastern history. Moving through different “Easts” and the West has helped me understand more clearly where we stand. It encourages me to read, reflect, and question history further. These interests, however, won’t directly manifest in my work, at least not in a literal sense.

I’ve been working on a new series for the past year. Moving away from familiar territories, I’ve been thinking about the elusiveness of the image. I’m making visual experiments by asking: Where do things begin and end? What qualities make a thing itself? And when those qualities are removed, what remains?

If I bring this back to the East/West framework: the West is built on an understanding where definitions and boundaries are clear. It draws its power from these clarities. When those boundaries blur, it becomes confused, even harsh. Even Western abstraction is highly defined; modernist abstraction doesn’t stretch far back historically, and it lacks an ancient tradition. In Eastern cultures, meaning emerges from ambiguity. Abstraction is present in every practice, it isn’t isolated from life. Naturally, this reflects in language. Language is one means of communication, but not everything. What is unsaid matters as much as what is said; what is not shown matters as much as what is shown. Semiotics was constructed within a Western framework, and part of my aim is to erode those rigid bonds.

Q: Your practice often engages with political, cultural, or conceptual ideas as the starting point. How do you translate those philosophical ideas into tangible form? And what role does language play in your practice?

A: This notebook is essentially a compositional exploration of the rhythmic forms of different emotional states. It emerged as a sequence. While observing my emotional responses to situations that occupy my mind and body, I allowed myself to be pulled in various directions and then documented those movements. It’s not a methodology I usually work with. I feel exposed when I externalise these states of delirium so transparently. My work usually involves partially concealing that nakedness, rather than showing it outright. That’s why I rarely keep such experiments in their raw form. This notebook became, in many ways, a neural map—something meant to be felt first through the nerves.

Q: Finally, can you tell me a bit about your notebook for the Creative Minds Project?